“At the end of the day, a filmmaker’s most important tool is humanity” – Ryan Coogler

The story is probably too familiar now. It involved a black boy by the name of Malcom Little. When a white teacher asked him what he thought of becoming, his young mind sparked with imagination: “Well, yes, sir, I’ve been thinking I’d like to be a lawyer.”

Leaning back on a chair and clasping his hands on his head, the benevolent teacher half-smiled and told him, “Malcolm, one of life’s first needs is for us to be realistic.” Paternalistically, he explained that in such day and age it was not realistically for a black person to be a lawyer. So, the black had to imagine something else. In fact, the teacher started imagining for him.

Ironically, that is the same year that a young black lawyer, Thurgood Marshall, won a US Supreme Court case that is now immortalized in the film, ‘Marshall.’ Yet in one conversation the imagination of a black boy was shattered. Of course, that ‘Boy Wonder’ grew up to be a legend. This is how he then interpreted it:

“I know he [Mr. Ostrowski] probably meant well in what he happened to advise me that day. I doubt that he meant any harm. It was just in his nature as an American white man. I was one of his top students, one of the school’s top students – but all he could see for me was the kind of future ‘in your place’ that almost all white people see for black people” – Malcolm X

Note the keyword ‘future’ for the new blockbuster on the block, Black Panther, is an Afrofuturism film. To put it simply, that is an attempt to imagine possible futures for Africa and its Diaspora. You may wish to call it the SciFi of an Africana – or even Black – World.

That is why it is important not to limit the film by the tyranny of the experts’ imaginations. For sure, we cannot agree about it. There are those who draw from it a great sense of black affinity. For others, it is another painful source of black anguish. Yet to some ‘souls of black folk’, it elicits a nagging feeling of ambivalence. And all that is okay given our varying points of experiencing intersectionality.

I, for one, find the gullible use of the term ‘tribe’ that African scholars have fought hard to deconstruct disappointing. The patriarchy of ‘absolute monarchy’ is also appalling. One cannot help but also be sympathetic to the critiques of the demonization of Killmonger who is the closest character to what Malcolm X or Black Panther Party members were in their radical attempts to bring black – if not global – liberation. All that matters but they should not cloud the positivity of representation captured below:

“I tell you it’s amazing, the impact of imagery and representation. It’s no small thing. Think about how these portrayals could truly affect the minds of these young children and their sense of esteem” – Danai Gurira

Thus, what should also matter as we continue to reflect and review it, is to let a thousand flowers bloom as we imagine the future – nay, futures – of Global Africa. Even if the movie is part and parcel of the corporate capitalism of Hollywood, at least let us not deny it its ‘revolutionary’ or ‘liberatory’ credentials. Part of its heritage is what Jelani Cobb refers to as “an entire lineage of that pan-African tradition insisted on was a kind of democracy of the imagination.”

Such was the democracy that Malcolm X was denied when he was Malcolm Little. Now it is partly possible for the likes of him to practice it. After all this is what the ancestors behind the lineage Cobb is referring to imagined it, that is, “If the subordination of Africa had begun in the minds of white people, its reclamation, they reasoned, would begin in the minds of black ones.”

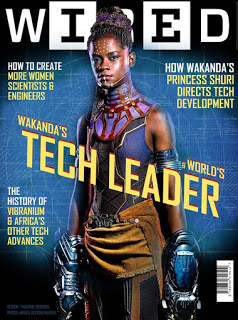

Yes, let ‘black nerds’ like Shuri imagine they can use technology responsibly and save the future of Africa and the world for that matter. Why not? Surely one can hardly dispute Chrystal M. Fleming’s argument that in Black Panther there is “a colonized vision of progress over-determined by Western technocentrism.” As she further puts it, defining “civilization and the value of human beings in terms of technological advancement” endangers the earth.

For her, “all of this points to the limits of our collective imaginations, the constraints we face in representing black liberation when our concepts are always, already thoroughly infused with colonialism, capitalism and even more ancient hierarchical ways of defining human worth.” I concur.

But should we now throw the tech baby with the technocentric bathwater? No! All we need is to both decolonize and democratize our technological imaginations. And Black Panther is not simply presenting us with a “technocentric Wakanda.” With its seemingly glowing flowers of life, it is highlighting the need to preserve the soul of the earth. Even its way of preserving vibranium is pro-life.

Rather than limiting our imaginations, Black Panther is more of an invitation to keep dreaming and imagining. And this is what the likes of Cobb and Fleming are doing in imagining other futures in their responses and reviews. It is what its sequel, I imagine, will do.

Malcolm Little, like the black boy at the end of the film, would feel anything imaginable is possible. If black Wakandans can make such a transformative spaceship for uplifting an ‘LA hood’, why shouldn’t he? That is its ‘black power’– to empower what the late Abiola Irele refers to as the core task of The African Imagination.

Black girls and boys can because black women and men could.