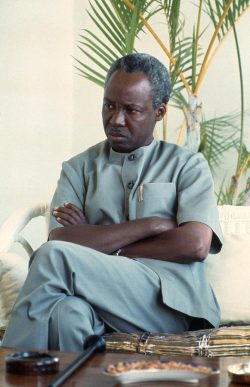

History has a funny way of repeating itself over and over again. The speedy intervention of President John Magufuli on the financial sector has even left some of our leftist intellectuals awed. It is as if the first president of Tanzania, Julius Mwalimu Nyerere, has returned.

Tanzania founding president, Julius Mwalimu Nyerere

The times have changed. But the challenges are more or less the same. In the beginning of his presidency, Nyerere, like Magufuli, had to deal with pompous leaders who hardly cared about financial responsibility. In an otherwise sympathetic take on ‘The Critical Phase In Tanzania 1945-1968‘, Cranford Pratt had this to say:

“A High Commissioner ignored financial regulations and ordered an official Austin Princess motor-car which he felt the dignity of his office required. A junior Minister spent public funds to rent herself a Jaguar for a holiday weekend while in Britain. A Minister drew a generous daily living allowance while on a foreign trip, even though his expenses were fully met by the host government.”

It is important to recall that, unlike Magufuli, Nyerere was heading a country that was openly trying to become egalitarian. Yet it had some leaders who had no problem with inequality. They were bold enough to even defy one of the most strict presidents the country has ever had. Pratt thus recalled how they frustrated his friend:

“The Minister of Regional Administration ignored a Presidential instruction and ordered seventeen Mercedes-Benz for the Regional Commissioners. Ministers sought a gratuity of twenty-five per cent of their total salaries because they had no job security. The issues were often minor, even petty, but they revealed an acquisitiveness that was discouraging to Nyerere. ‘Enough! I do not want to see this file again’, was his angry, perhaps even desperate minute in regard to one of the minor ministerial abuses of his office.”<

Being angry or strict, as Nyerere learned very early on, was not and could not be enough to ensure that leaders do not fail to adhere to what Professor Ernest Wamba refers to as the “principle of fidelity” in his definition of corruption. A country cannot simply depend on the good will of a person. Integrity has to be institutional(ized).

Take, for example, the case of the four officials of the Prevention and Combating of Corruption Bureau (PCCB) who were recently suspended, ‘allegedly’, because they defied the presidential order of not travelling abroad without a permit from the Chief Secretary. As a bold attempt at curbing recurrent expenditures, the presidential directive is laudable. But the question lingers: Could they do so if there was a ‘decentralized’ institutional setup to prevent this in the first place? What if their Director General gave them a go ahead?

As far as technocracy is concerned, it is thus refreshing to note that the president has appointed a Minister of Finance who is said to be ‘Mr. Nonsense’ when it comes to fiscal discipline. However, from the point of view of ideology, as we have observed about ‘The New Minister of Finance and the Fiduciary Future of Tanzania‘, it is justified to be wary of ‘a World Bank Man‘. Nevertheless, if there is anything useful to take from its contradictory institutional legacy, it is this critical stance on the salary increase in 1961, which “added £ 1,100,000 to the government’s wage bill”, as Pratt captured it:

“[Nyerere] noted that the World Bank report had said that the Tanganyikan government could not expect to raise its revenues by more than £ 1,000,000. He went on to argue that ‘if there was a person on the moon and he had taken the World Bank Report…and taken the recommendation of the government and put them side by side, he would say ‘this government!’ An intelligent mission tells us that they cannot raise their revenue by more than £ 1,000,000 and they are handling all this £ 1,000,000 to their civil service. They must be in serious love with their civil service.”

Surely all our civil servants have to, and must, be paid well so that they can perform better and remain in (public) service. This is especially important given that some of them are attracted to the private sector. However, there has to be a balance between the revenues that we collect and the salaries that we pay. Moreover, their earnings should resonate with those of our main producers.

Recent debates about the salary of the celebrated Director General of the National Housing Corporation (NHC), Nehemiah Mchechu, is instructive in this regard. In responding to accusations that his salary is exorbitant, he asserts that it is lower than the alleged amount of Tsh 36 million. He also argue that he was paid more money in the private sector but opted to accept a lower salary in the public sector for the sake of rebuilding it and serving the country.

Mchechu also reminds those who query his salary about the amount of money he is enabling the government to collect. Elsewhere, in his exclusive interview with TanzaniaInvest.Com, he notes that now, being five years since his appointment, NHC “boasts of a balance sheet of around USD 2 billion.” It is quite possible that he is under attack because of his potential of becoming one of the leaders that would aid Magufuli in his quest to fill public coffers. Nonetheless his case of traversing the private and public sectors can help us understand what is at stake in instilling fiscal discipline.

When leaders started being distracted from paying attention to their public responsibilities in the 1960s by engaging in private company directorship and construction of houses for renting, the solution was to institutionalize the separation of leadership and business. As Pratt noted, this came in the form of these prohibitions for middle or senior leaders that were ‘adapted in/by’ the Arusha Declaration:

“(1) holding shares in a private company; (2) being a director of a private company; (3) receiving more than one salary; (4) owning one or more houses which are rented to others….”

Lest we trash them as being outdated, let’s revisit this recent case:

“[Mchechu] Anasema kuwa kuna baadhi ya vigogo serikalini na watumishi wa shirika hilo waliokuwa wakiendesha ukodishaji wa nyumba kwa mikataba ya kilaghai na NHC kwa kulipatia fedha kidogo wakati wanatoza fedha nyingi kwa wapangaji [Mchechu says that there are some big shots in the government and NHC officials who were renting houses by using dubious contracts with NHC, making it collect little rents while they got a lot of money from tenants]”

Discipline in matters of public finance can thus not be addressed without tackling the thorny issue of ‘conflict of interests’ among leaders. The fact that the country’s policy-cum-ideology continues to be ‘market economy’, as President Magufuli has reiterated in his recent meeting with the business community, is not an excuse for leaders to conflate private interests and ‘public interest’. We need to be assured that our public and their private spheres are separated.

Yes, the public need to be sure beyond any reasonable doubt that a leader of a parliamentary standing committee responsible for public companies, such as the Air Tanzania Company (ATC) Limited, is not using his position to make a quick profit for his private aviation company. We need to be sure that a leader of a similar committee responsible for energy and minerals is not using the information and connections there to benefit his/her own private mining pits or an electric power generating plant. And the list goes on and on.

Critics of the concept of ‘conflict of interest’ would ask: ‘But how can you really be sure?’ By ensuring that no such persons hold such positions of leadership in the first place. In this regard, the question is not simply about declaring your ‘conflict of interests’ and then staying on to safeguard them right there. Rather, it is about having to opt out of something public because of vested personal interests.

Perhaps these critics, who apparently view this concept from a leftist vantage point of ‘class analysis’, might find Lionel Cliffe’s Marxian take on ‘Personal or Class Interest: Tanzania’s Leadership Condition‘ in the 1970s below palatable and applicable even today:

“….. Of course, in some countries, while it is not precisely admired, it is nevertheless accepted that political office will lead to business gain. In these circumstances, personal wealth can become a pre-essential as well as a by-product of a political career. In many Commonwealth countries, there is a general feeling that such overt self-interest should not motivate political decisions, and hence the ‘declaration of interest’ rule. Yet this rule refers to specific, personal interest, and in so far as it is concerned with questions other than the preservation of legality and personal integrity, it assumes that there is likely to be some conflict with the ‘public good’. If one think further of the kinds of specific circumstances in which the declaration of interest is likely to occur, one realizes that often the possible deflection of benefits or resources would be against public interest because it offends against the notion of free competition-such as the awarding of tenders, pricing of purchased properties, etc…. To this extent the declaration of interest rule usually precludes the possibility of personal interest dictating the distribution of favours or services. However, where this rule operates, those making the decisions are not precluded from making decision which benefit the broad social categories to which the majority of them might belong. An MP may not take part in a vote on an issue affecting the award of some contract, say, to his company; he is, normally, a party to decision about the level at which his company – and all others – will pay tax….”

Our country cannot afford to easily let off the hook our leaders ‘both ways’. While a market economy may continue to make them part and parcel of the ‘political-cum-business elite’, we can at least ensure they are disciplined enough, fiscally, by separating personal interests from public interests. It can be done, albeit, institutionally.