Cuban revolutionary Commandante Fidel Castro’s passing was not a sudden shock for the world nor for us here in Africa. We already knew he was unwell and at his age, we knew that his revolutionary life was near its end. He even let us know it and advised that the ideas of the Cuban revolution will go on long after he has passed. Those ideals, much maligned by American media and its presidents bar Barrack Obama, were unapologetically socialist. And by dint of their humane precepts also African.

And Africa knows who Commandante Fidel was. And even if one is not part of the liberation struggle generation of the continent, his name was at some point whispered, his political exploits and his colossal revolutionary reputation referred to in our schools, universities and progressive political organizations. Even where we resided in our African countries that were avowedly anti-socialist and in the ambit of the West during the Cold War, we knew that if you mention Fidel, you mention a revolutionary.

My first encounter with his world, his thought, his country was not through a book. It was through a Zimbabwean teacher who had recently returned from Havana to teach us chemistry in high school. Sometimes the chemistry was difficult but the admiration the teacher had for Cuban society was self evident. In fact it was idealistic to a fault. I didn’t understand socialism or communism proper nor why in any event, there was such a chasm between USA and Cuba relations. Even after skimming through the history books of the Cuban missile crisis.

Encountering Fidel at university was a different ball game. In the late 1990s, with the Cold War effectively over and all but one African country being free (remember the Saharawi Republic), it was all about Fukuyama’s infamous ‘end of history’ dictum. We were taught, not all the time, that communism is dead and liberal democracy and economics are the definitive fulcrum of human (western) history. Yet the lecturers couldn’t fully explain the stubborn island that was Cuba in this lexicon. But we would debate it at International Socialist Organisation meetings at the University of Zimbabwe Campus. As wannabe revolutionaries we would cite all the Lenins, Fanons, Nkrumahs but eventually end up referring to a living revolutionary in the form of Fidel Castro in awe at how he could possibly be holding ‘socialist fort’ on the island that was Cuba.

Overwhelmed by economic structural adjustment programmes and forlorn about the receding global possibility of global socialism, we would debate Castro is smaller spaces and occasionally watch video cassettes of Cuban life and his very long speeches.

The South African and Namibian comrades, that we would meet as activists at the turn of the century, would perpetually remind us of the painful but legendary battle of Cuito Cuanavale and how it was the Cuban defense forces that helped not only spur on their struggles but prevent apartheid South Africa from having a stranglehold on the region.

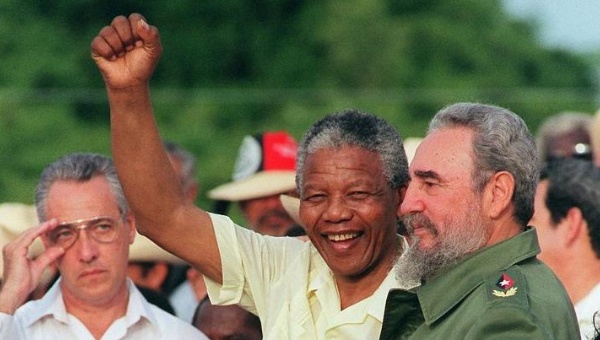

And we were perplexed at why the American media at some point raised eyebrows about African struggle icon Nelson Mandela’s state visit to Cuba. We knew the Cuban people had helped us throw off the shackles of colonialism, settler states and apartheid. We knew of the Tri-Continental conference that occurred in 1966 that Fidel hosted in Havana after Che Guevara’s abortive trip to the then Zaire. We know he met and was impressed by the African revolutionary Amilcar Cabral at that meeting that re-enforced his revolutionary commitment to assisting African liberation struggles from colonialism.

He was also to meet a majority of African liberation and post independence leaders inclusive of icons such as Samora Machel and Julius Nyerere among others.

And he didn’t end there. He continued, at great cost to his own country to assist Africa in health and education. And he continued to be a moral voice against the imperialism, neo-liberalism, liberal interventionist wars and global unilateralism that has characterized the post Cold War global order. As Africans we knew that Cuba’s differences with America were not our creation nor ours to solve. But like the solidarity that the Cuban people gave to us we returned it at the United Nations and other global for a. Not in obligatory gratitude but more form the lived experience of how our humanity binds us together regardless of race, colour, creed or continent of origin.

And yes we read the biographies, watched the movies, documentaries and even witnessed a handshake between Raul Castro and Barack Obama at Nelson Mandela’s funeral. We saw the continually negative coverage of Cuba (as will be the case during Fidel’s memorial services) in the now global media and argued over why his socialism wrongly curtailed freedom of expression. But there is one thing that we as Africans will always know, from liberation generations to post independence ones and post Cold War ones. This being that African liberation struggle history is clear. To paraphrase his treason trial courtroom speech in 1953, ‘condemn him, it does not matter,’ our African struggle history absolves him.