Kenyans have long challenged power by laughing. But the Kenyan government has started cracking down on humour.

“At a time like this, scorching irony, not convincing argument, is needed,” declared American abolitionist Frederick Douglass in an 1852 speech. He was referring to the futility of arguing the wrongfulness of slavery to a nation whose founding documents declared liberty as a fundamental right. Rather than try to persuade his audience of the obvious, Douglass deployed humour as both a buffer and a weapon against the absurd inconsistencies of enslavement in 19th-century America.

But he may as well have been speaking about modern-day Kenya where each new day appears to bring new governmental absurdities. Since last weekend, the police have taken to closing major thoroughfares in the capital, Nairobi, under the pretext of enforcing a COVID-related curfew, causing massive, hours-long tailbacks.

Caught up in the ensuing traffic chaos have been ambulances ferrying patients as well as other emergency vehicles, parents with young kids, and employees rushing home. In response, Kenyans have turned to social media to express their outrage, many couching it in satirical diatribes.

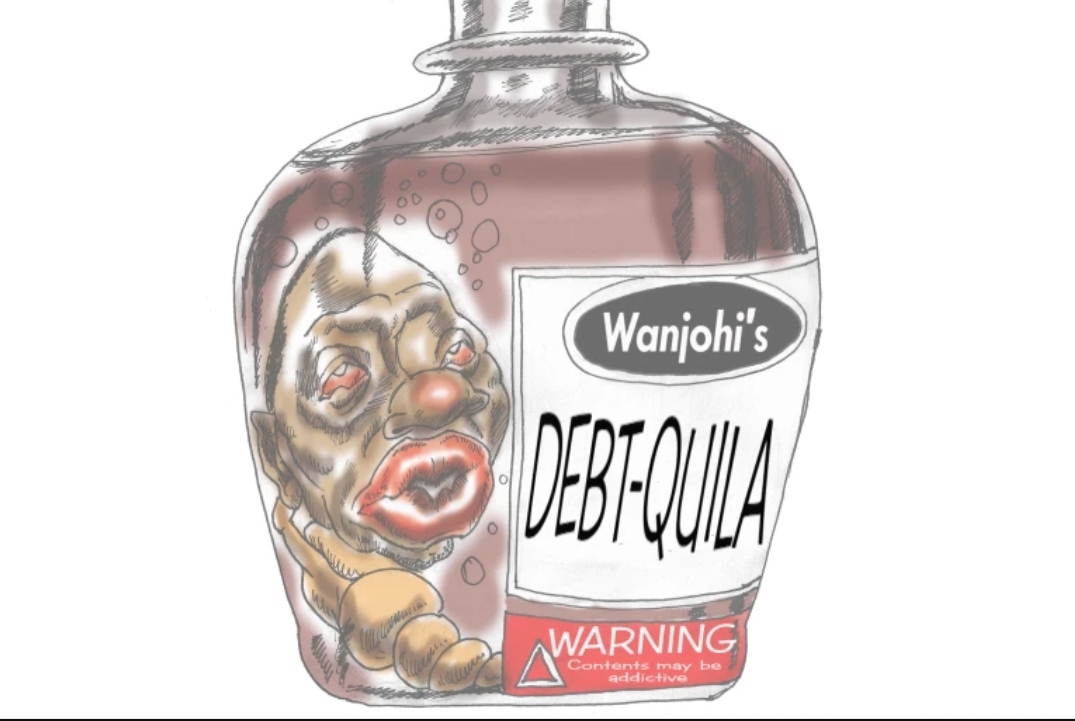

Humour and satire have become a favourite means to visit torments upon the kleptocrats and incompetents in power. But the Kenyan state is not laughing. Two weeks ago, as Kenyans online fulminated against the government’s latest attempts to procure loans from the International Monetary Fund, activist Edwin Mutemi wa Kiama was arrested by police for circulating a poster – a parody of common newspaper notices posted by firms after they fire employees – which declared that President Uhuru Kenyatta was “not authorised to act or transact on behalf of the people of Kenya”.

In court, prosecutors declared: “The presidency is a symbol of unity and any attack on him on the institution is contemptuous,” and asked for Kiama to be kept in jail for two weeks while they worked to set up a charge. In a ridiculous and widely panned decision, the magistrate instead slapped him with $4,600 cash bail, more than two years worth of wages for the average Kenyan, and forbade him from discussing Kenya’s foreign debt or the president online.

The fifth rule in American activist Saul Alinsky’s classic on grassroots organising, Rules for Radicals, states that “ridicule is man’s most potent weapon. It is almost impossible to counterattack ridicule. Also, it infuriates the opposition, who then react to your advantage.” True to form, the state’s over-reaction to the ridicule worked to Kiama’s advantage, exposing its intolerance and brutality and inspiring even more online memes and derision.

Throughout their modern history, Kenyans have had to learn to wield humour when dealing with the absurdities of the state. “I think it is undoubtedly true that laughter was – for many Kenyan audiences – a means of depriving missionaries and officials of attention, reverence, and authority,” says Derek Peterson, professor of history and African Studies at the University of Michigan, speaking of colonial Kenya.

Whether it was uproarious laughter during church services and prayers to frustrate missionaries’ attempts at conversion through a specious dialogue of faiths, or cracking jokes about their “predicament at the hands of unreasonable people” within the torture camps set up by the British government, humour was a constant feature of resistance to colonial domination.

Following independence, and especially during the despotic 24-year reign of Daniel Arap Moi, satirists from playwrights to novelists to columnists to cartoonists led the charge to recover rights from the state. As the state receded, the satirists grew bolder.

Today, with the advent of the internet and social media, it is a rare day when one does not come across biting tweets, memes and cartoons lambasting the personal and public failings of President Kenyatta and his acolytes. For example, there has been a proliferation of new monikers for the president, mocking everything from his widely assumed proclivity for booze to his dressing choices to his sheltered life. Indeed, Kenyatta himself has blamed the incessant lampooning for his decision to flee Twitter.

Much hinges upon who will win the war between the state and the satirists. All previous incarnations of totalitarianism, from the British occupiers to Moi, relied on a cult of invincibility and omnipotence to cement public acquiescence. As Kenyatta attempts to rebuild his father’s brutal and centralised dictatorship, a determined mass of Kenyans is working to deny him the intimidating aura and stature he craves, cutting him down to size at every opportunity. The democratisation of satire by the internet and social media makes it much more difficult for the state to either control or ignore them.

So far, it has periodically turned to the law and the courts in an attempt to bludgeon critics into silence. In December 2014, a prominent blogger, Robert Alai, was charged with undermining the presidency after tweeting that Kenyatta was an “adolescent president”. A month later, a university student, Alan Wadi, was sentenced to two years in jail after calling Kenyatta “a criminal [marijuana] smoker and unfaithful red-eyed man”.

In more recent times, several bloggers and journalists have been prosecuted for publishing what the government deemed to be misleading information about COVID-19, which it said amounted to incitement of the public against the government, or for publishing corruption allegations.

All these are worrying signs. The satirists are Kenya’s canaries in the mine, testing whether the air is fit for democracy and free speech. If Kenyatta succeeds in silencing them, Kenya’s democratic dream will die with them.