For the tenth time in a decade, global champions of digital culture met in Berlin. Known as Re:publica, the conference “has grown from a cozy blogger meeting with 700 participants in 2007” into nearly 10 thousands. As a member of #AfricanBlogging interested in land rights, one keynote was of particular interest.

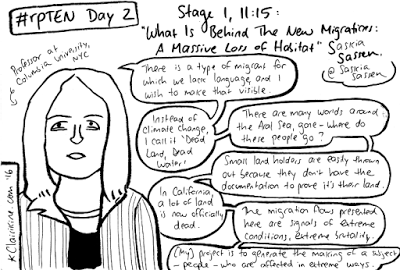

As Professor Saskia Sassen was delivering a keynote on “What is behind the new Migrations: A Massive Loss of Habitat” to a packed audience full of ‘netizens’ I wondered: What would they find so interesting about what hardly affects their ‘cyberspace’?. It was only after listening that I came to realize why land as habitat should matter to anyone who inhabits any part of our globalizing world. After noting that we are familiar with war refugees and migrants, she notes that there is third type of migrating subjects. To make them visible one has ask the question: “Why are they moving? There is no war where they are coming from.” One of the causes for this, according to her research, is the “making” of “dead land, dead water.”

This deadening goes hand in hand with the expansion of mining, land grabs and cities to force people out of their habitat. For her, the “pretty” language of climate change is not adequate to capture it. Unlike those who claim that “land grab vocabulary, with its connotations of ‘illegality’,” distorts “understanding of investment”, Sassen states:

“And we are talking of people who have been in that land for centuries…but they don’t have the papers, they don’t have the instruments to show that this is my land. So, they can be thrown out. The estimate is: Every year, three million…. The main argument that I want to make is: They are invisible to the eye of the law….”

Such ‘legal blind spots’ enable us to look beyond the law. As we noted in 2009, legal discourses on land have been used to render such people “wavamizi”, a Swahili term that literally means “invaders”, to justify their eviction. We also noted in 2010 that:

“It is tempting to conclude, alongside fellow strong critics of land grab such as the Land Equity Movement in Uganda (LEMU) and ILC, that land grab implies accumulation of land holdings through illegal and/or illegitimate means or simply ‘means deliberately and illegally taking away someone else‘s land rights’….

But this conclusion has to be qualified as there are incidences whereby land acquisitions in the light of the domestic policy frameworks and legal systems are sanctioned. As such there are at least two typologies of land grabs, that is, illegal and legal – or more appropriately, legalized – land grabs. In the case of Tanzania, land grabs, especially those of ‘village land’, are legally sanctioned through procedures for land acquisition.”

“Now land grabs have long existed. The United States use a lot of land in Kenya, for instance, to raise cattle because cattle is quite destructive, we know that. Kenya has vast stretches of dead land thank you to the United States…using that to grow cattle, same thing as Central America – lot of dead land. So, we have been killing land for a while but there is so much of it. It is shrinking now…. Here are some figures [From 2006 to 2010: 220 million hectares of land in Africa, Latin America, Cambodia, Ukraine etc. bought/leased by rich government, firms, financial firms]. The estimate now is that there are over 300 million hectares of land that has been bought.”

In her words, such figures indicate that the “land is now more valued than the people or activities on it.” Hence “what we measure as development”, she argues, “is a massive expulsion.” It is “the making of surplus population.” Sassen elaborates:

“There are about 100 firms…and about 15 governments that does include the United States but also includes Saudi Arabia and China etc…who are buying land mostly…to develop plantation agriculture…and you know plantation agriculture is a bit destructive of land, right, it does not enable land to have earth, to have a long life. Smallholder agriculture knows how to keep that land growing for millennia. Plantations, no way – that is not the plot. It is pesticides and fertilizers, you know, to get huge – to get it growing fast and it all has to look beautiful…it is a lot of chemicals and stuff like that. Now what happens here is that smallholders, and you know this, they don’t necessarily have documents that says this is my land, I have been living here, my family has for centuries …they are easily thrown out…”

Although she acknowledges that the figures are the highest in Africa, Sassen also notes that they are also growing elsewhere. What is so revealing is the way her examples captures the link between the Global North and the Global North:

“This is about Europe now. Land grabs in Europe…. The sons and daughters of former farmers in France, given the bad job situation (this is something that happened 2 or 3 years ago), decides that ‘maybe the best bet for me is to go back to the countryside and buy some land and some very specialized farming….’ Guess what? No land for sale. It has been mostly bought up by large corporates. Saudi Arabia has more or less bought up – and the Qatari – Bosnia…. Last example… A nice Swedish firm…. has bought a vast stretch of land in Northern England….”

For keen observers, such dynamics explains why these Euro-American entities are public-private partners of the Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT): Monsanto; Royal Norwegian Embassy, SNV Netherlands Development Organisation; United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Clinton Development Initiative, Stiching IDH Sustainable Trade Initiative, Syngenta, Nestlé, International AG, UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) etc.

In regard to bio fuel, Sassen argues that “growing crops that are not going to be for eating, so, you have no constraints on the amount of pesticide…poisons…you are making that land dead.” She thus decries the tendency of moving on to develop another plantation after twenty years or so after degrading the previous one. As for water grabs, she cites the cases of Nestlé and Coca Cola managing to “exhaust two underground water tables in particular areas of India” thus causing deprivation.

So, what does digital culture have to do with all this? I think in this age of ‘Google Earth’ and ‘Big Data’, our champions of bridging the digital divide can be helpful in providing empirical evidence on the scale of such grabs. Doing so will help those who are not so visible to counter the claim that “Land grab fears have been exaggerated.”