I have worn my hair in a messy afro for most of the last six years. It was the easiest way to survive dark days in college when I couldn’t be bothered to remove the three little twist braids from an all-night of reading. It was convenient and provided less heat in Kampala, allowing me to stand under the shower whenever I needed to.

Of course, there were lots of comments. A lot of “Are you seriously leaving the house like that?” from the sisters to sighs from my mother. Eventually they would decide that college damaged me too much and now they had a mad sister/daughter. “That is how she is,” they started to explain to friends. And later in the workplace, they would tell me “but that is how you are” as though this should never be contested, when I would relate to something a colleague had said.

My family’s main contention though, was not that my hair was natural. It was that I refused to mould its naturalness into a socially acceptable form. There were many options for my kinky African hair, they felt. I could blow dry it into a ponytail, braid it or learn like they did to take care of permed hair.

But was it political?

No, not at the beginning. My hair choice quickly became political because I had to defend it. Every. Single. Time. Because unfortunately, the world is not structured to celebrate, or even to allow, the existence of a black woman’s hair. It must be explained because it is not normal. It is assumed to be political because it goes against the expected codes of being. And when many embrace it, everyone side-eyes and starts to tsk and say “young women these days…”.

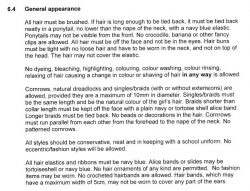

Last month, the students of Pretoria High School for Girls protested the school’s code of conduct that basically deemed afros “untidy”. One student is quoted in The Guardian saying that a teacher told her her afro was “distracting others from learning.” The protest, by the brave high school girls, received attention and many concerned people took to Twitter with the hashtag #StopRacismAtPretoriaGirlsHigh.

The code of conduct is available for download on the school’s website. It does not specifically state that the Afro is banned. It does state how hair should be worn, and none of them are compatible with the afro that cannot be “tight with no loose hair” or “be worn in the neck, and not on top of the head.”

This can be taken a little further to the need to police people’s bodies under the guise of rules, and for girls’ schools especially, “neatness.” In my own high school here in Uganda, we were not allowed to run or walk on grass. The calm girls walking around the compound, with the lush green undisturbed lawns might have been impressive to visitors, but what does it mean for the bodies that we force to do all this? Because these are rules that are enforced on the very body of a human being.

Before anyone defends the walking and preservation of the lawns, I should state that my school was missionary-founded and was started for the purpose of educating girls enough so that they might make good wives and mothers for the men that were coming out of the boys’ schools (the boys were educated to be clerks for the colonial government). And we dare not have a wife who runs and jumps over benches, or even dares to raise her voice across the room. There was no place for such in the world.

Schools have continued with this fabric. The Pretoria High School for Girls only started admitting black girls after the end of apartheid in 1994. And while they may be admitted, do they have a place in the school? Can they exist in the system without folding their bodies (and hair) into an acceptable code that refuses to recognise them?

For these girls- and all African women, natural hair is not fashion. It is not a style. It is how hair comes out of our heads. That’s how it grows. Its least manipulated form is probably the afro. And yet, it continues to be a political choice because we have to continuously prove to the world that we belong here- and we should not have to twist ourselves into an acceptable form first to take our place in the world.

By Rebecca Rwakabukoza from Uganda.