It was both distressing and soothing to read Takura Zhangazha and Paul Shalala’s reflections on our recent trip to Gorée Island in Senegal. Distressing because of the constant reminder about the gory legacy of slavery. Soothing because of their optimism about the glorious outcomes of the enduring struggles from enslavement.

The island, as Shalala keenly observes, is a reminder of “how fragile human life can be when those in authority do not respect the rights of those they lead.” And, as Zhangazha aptly puts it regarding such visits, “there was always going to be a significant pause for thought, pained emotion and a sense of liberation.”

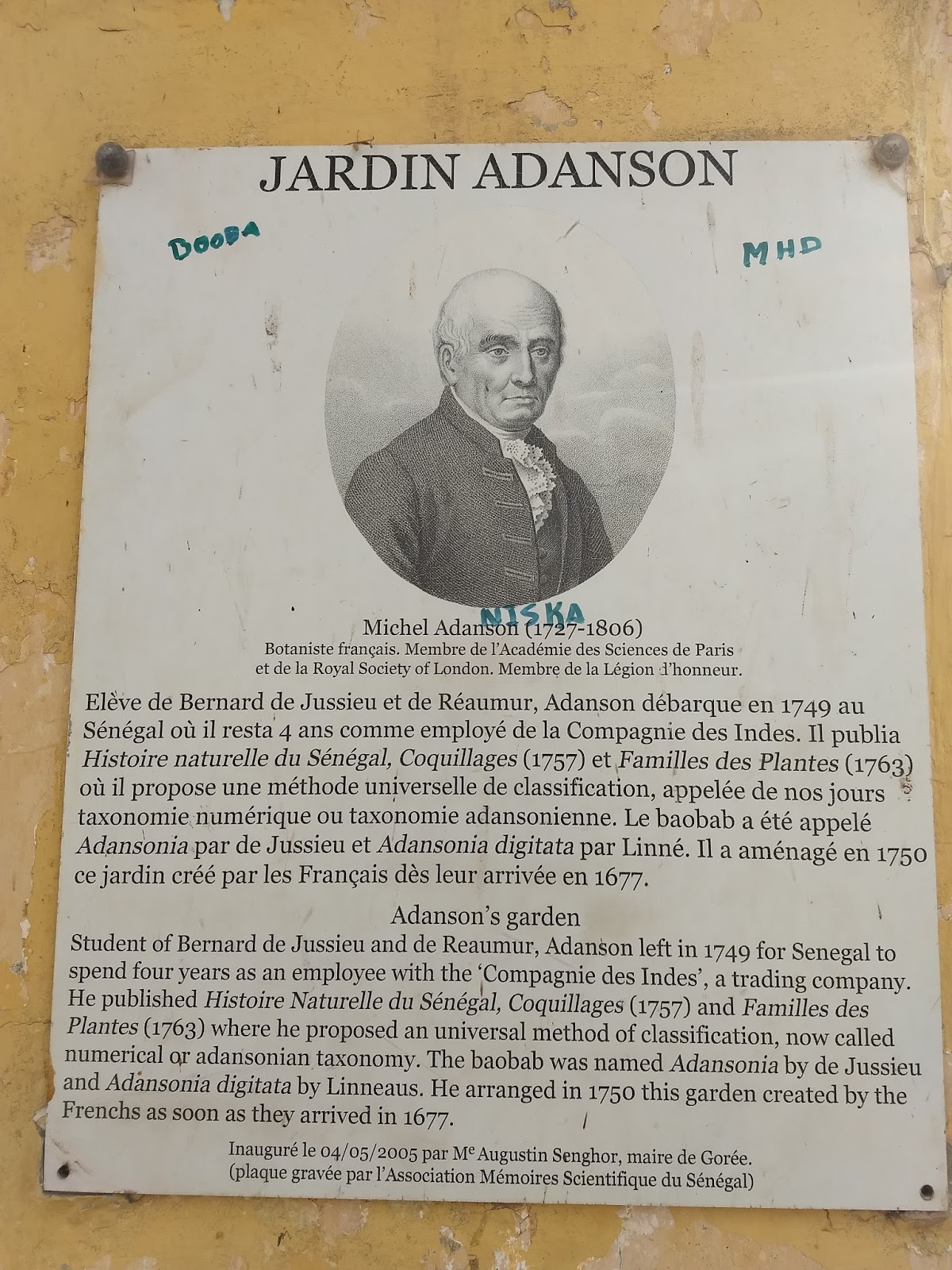

One such moment came when I stumbled on an inscription of Michel Adanson. He is described as a student of two naturalists who “left in 1749 for Senegal to spend four years as an employee with the ‘Campagnie des Indes’, a trading company.” This is none other than the French East India Company that was instrumental in the ‘birth’ of capitalism and the slavery that fed its (initial) ‘rise’.

His inscription caught my eyes because I had just completed a dissertation chapter on the history of capitalism in Africa that draws from Mary Louise Pratt’s critique of naturalists. She argues that their collective works and debates contributed to the birth of ‘scientific’ racism. It is this ‘Linnaean Watershed’, a term for the historical period derived from the name of a leading naturalist, Carl Linnaeus, that led to a fusion of racism, capitalism and colonialism.

Critics of Pratt may wish to note that her core argument is not that naturalists had to agree with Linnaeus to be part of the watershed. One only had to be part of the collective discourse of classifying people and plants hierarchically. Adanson even “presented Linnaeus with a number of plants from his collection before the break in relations over their competing systems of classification.” No wonder they became rivals. Yet, as the inscription above notes, Linnaeus named the baobab that continues to grace Gorée Island today “Adansonia digitata“.

Although one writer asserts that Adanson “entered the service of the French East India Company in order to study the natural history of Senegambia”, it must have dawned to him that he had to also be an accomplice in slavery and racism. However, another writer indicates that he “formed the project of a settlement on the African coast for raising colonial produce without negro slavery, which the French East India company refused to encourage.”

One sympathetic writer is critical enough to quote Michele Duchet who “stresses that Adanson’s voyage to Senegal had more than a scientific purpose” as “they are fact-finding missions in the broadest sense of the term” whereby the “result of his travels is not only the natural history of Senegal, but also secret memoirs under the direction officialdom, to be found side by side with archives of other colonial administrative memoirs, as elements of the same dossier.” This writer who happens to be Xavier Carteret then cites this evidence from André Bailly that captures his colonial ideals:

Yet Carteret’s sympathetic reading reiterates this query: “What, in Adanson’s mind, were ‘free and voluntary slave[s]?'” Citing Jean-Paul Nicolas, Carteret then sharply observes that the “oxymoron stops us from seeing clearly, but another note scribbled in the same copy of the Encyclopédie is close to asserting an antislavery position. Adanson proposes to replace ‘slaves by deported criminals who bear a plaque stating the nature of their crimes, to be chained and to work in this hot country instead of black slaves.'”

For Carteret, the director of the French East India Company rejected Adanson’s proposal because their business “was, one suspects, strongly attached to black slavery.” One of the proof for this, he argues, is “the abuses of which the naturalist complained during his long stay.” This story leads him to distance the naturalist from the history of slavery. “While Adanson is silent on the issue of the slave trade on his voyage to Senegal—without doubt for strategic reasons concerning publication”, Carteret thus argues, “he shows himself immediately to be hostile to any form of racism.”

Strategic silence? For the sake of what? At the expense of who?

Pragmatic silence in the name of advancing ‘scientific’ knowledge can have a detrimental effect on humanity. Adanson may seem far removed from our contemporary history. But the dilemmas he faced and the choices he made were more or less the same as the ones we are encountering in our situation today with its modern slavery.

Zhangazha whom we started with reminds us that knowing “too that there are still contemporary actors that want to pursue this trade in Libya (and elsewhere) means the struggle against slavery is not over.” And Shalala who followed insists that we should move from “slavery to the promotion of reconciliation” and “peace.” Or, in other words, from the gory to the glorious history of Africa(ns).