By Joseph Kagiri and Mulama Mwila

Health is a critical part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The SDG 3.8 targets to “achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health care services, and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all,” it reflects the overall ambition of good health and well-being for all, at all ages.

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) catalyzes social inclusion, gender equality, poverty eradication, economic growth and human dignity. This inputs into SDG 1, which calls to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere”, without UHC, SDG 1 is at risk.

One of the indicators used to monitor progress toward UHC is Service Coverage Index (SCI), with countries having a value from 0 (no service coverage) to 100 (full-service coverage with all essential services).

UHC SCI is built from 14 tracer indicators, extracted from various sources and organized around four components of service coverage, which include: Reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health (RMNCH); infectious diseases; non-communicable diseases (NCDs); and service capacity and access.

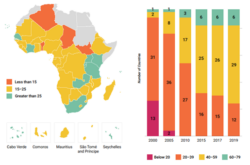

Based on the World Health Organisation (WHO) Report, Tracking Universal Health Coverage in the WHO African Region, 2022, in 2019, the UHC SCI ranged from 28 to 75 across the 47 Member States. Of these, seven had high service coverage (index of 60 and above), 29 had a service coverage index value of between 40 and 59, and 12 had low coverage (index between 20 and 39). No country had very low coverage (index below 20).

There has been substantial progress made in the UHC SCI over the past two decades across the WHO African Region. Based on the WHO report 2021, the regional population-weighted UHC SCI was 46 in 2019, up from 24 in 2000. Thirteen countries had a UHC SCI of under 20 in 2000, with only three countries with a UHC SCI above 40 then.

Source: World Health Organisation report, 2021

The most significant 2021t progress was observed in the Eastern Africa subregion (24 index points), followed by the Western and Southern Africa subregions (23 index points). Regarding the SCI subcomponents, the infectious disease subindex saw the most improvement between 2000 and 2019 (from 6 to 48), with a noticeable acceleration in 2005 due to the rapid scale-up of HIV, tuberculosis and malaria interventions. This could be attributed to significant investments by governments and development partners in the fight against the three diseases.

Although Africa has seen notable improvements in health outcomes, many countries face huge, unmet health needs, and pressures on health systems are expected to increase. There is also an urgent need to remove remaining barriers to enable access to health care for all.

Poor infrastructure, limited availability of basic amenities and weaknesses in the design of coverage policies to limit the harmful effects of out-of-pocket payments among the poor with chronic health services needs still hinder access to health care services across the continent. Other barriers include shortages and inefficient distribution of qualified health workers, prohibitively expensive good quality medicines and medical products, lack of access to digital and innovative technologies and threats from emerging epidemics.

Investment in Africa’s health systems is key to inclusive and sustainable growth and most African countries have integrated UHC as a goal in their national health strategies. This has led to the implementation of national health insurance schemes which are financed by mandatory deductions on the payslips of employees in the formal sector and increased government allocations in the health sector.

However, there is a need to ensure that the expanded domestic resource for health translates into equitable and quality health services and increased financial protection. For example, despite making hefty investments in the healthcare system, South Africa retains the highest death rate. This indicates that Sub-Saharan Africa is to move away from the ideology that investing more finances equates to improved medical service delivery, and also pay attention to the quality of health service provided if it is to attain UHC.

The COVID-19 pandemic has subsequently led to significant disruptions in the delivery of essential health services. Rising poverty and shrinking incomes resulting from the global economic recession are likely to increase financial barriers to accessing care and financial hardship owing to out-of-pocket health spending for those seeking care, particularly among disadvantaged populations.

The pre-COVID challenges, combined with additional difficulties arising from the pandemic, bring an even greater urgency to the quest for UHC.

Accelerating progress toward UHC in Africa is not a mirage, it is within reach, despite the financial challenges on the road to UHC and emerging pandemics, but will require political leadership and a clear strategic vision.

More than ever before, strong political commitment from world leaders and partner organizations is the essential ingredient for overcoming barriers.

The COVID-19 pandemic response has demonstrated why that commitment is so important, and why, as the world responds to and recovers from the pandemic, we must all pursue it with more determination, innovation and collaboration.

As stated by the WHO Director General, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus in his opening remarks at the Special Session of the World Health Assembly on 29 November 2021, “The COVID-19 pandemic is a powerful demonstration that health is not a luxury, but a human right; not a cost, but an investment; not simply an outcome of development, but the foundation of social, economic and political stability and security.” Strengthening health systems based on strong primary health care is pivotal to building back better and accelerating progress towards UHC and health security.

Some possible approaches that could aid the attainment of UHC include using a phased approach that makes primary health care and laboratory services universally accessible before taking other levels of health care access. This would allow for lessons to be learnt and measures are taken to improve any weaknesses at one phase before expanding the programme to another phase. Additionally, there is a need for prevention and control of communicable and non-communicable diseases taking centre stage by implementing health programmes to eradicate the diseases.

Governments also need to promote Public Private Partnerships (PPP) to enable the development of health infrastructure and training institutions. This will facilitate the growth of infrastructure while taking advantage of the efficiencies of the private sector.

With the lessons learnt from the Covid-19 Pandemic, the importance of enhancing preparedness for future pandemics so that the gains achieved in building health systems are not eroded cannot be overstated.

Joseph Kagiri is a Senior Manager, Government and Public Sector, at PwC Kenya & Malama Mwilwa is an Associate – Transactions Advisory services, at PwC Zambia.

Cover Photo from Pexels.