“The good men do is oft interred with their bones.” These were the words of Mark Antony from his emotional speech at Julius Caesar’s funeral. In translation, Mark Antony is saying that good deeds often go unheralded, or even when noticed, they fade away in people’s memories so that they die with them.

It’s a means of observing that good people are many, but that the memory of what they have done for the world often vanishes, but those who have committed evil deeds tend to be remembered for them.

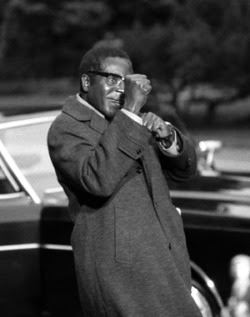

Such is an example to describe Zimbabwe’s former president, Robert Mugabe, who died last week in Singapore at the age of 95. His legacy has drawn a lot of debate with contrasting narratives at any given time throughout his life and controversial 37 years in power. Often in life, there are rarely things that will capture people’s imaginations for very long and one has to be reminded of them over time in to order remember.

While many of us were not yet born during the World Wars, we know of names like Hitler and Stalin because of the evil things they did during these wars. Their actions were sufficiently impactful to traumatize a generation and have consequences for those that followed. This is how many Zimbabweans are remembering their former president who disenfranchised a whole citizenry because of his selfishness and grip on power.

However, as the debate on Mugabe’s legacy rages on, his story and his legacy are not different from that of Okonkwo, a character in Chinua Achebe’s 1958 epic novel, ‘Things Fall Apart.’

An analysis of Okonkwo’s character strikes some similarities with Mugabe, from their upbringing until their demise. Those who read Achebe’s classic would know of a strained father and son relationship in which Okonkwo grew up hating his father and consciously adopted opposite ideals. As for Mugabe, his father abandoned the family when he was 10, leaving him to deal with a mercurial and emotionally scarred mother, according to Heidi Holland in her book: Dinner with Mugabe (2008). Mugabe had a strong resentment towards his father whom at one point he mockingly described him as a ‘polygamous’ man who abandoned them and went to Bulawayo where he got a ‘beautiful’ woman. This explains so much about these two’s adult characters.

Consequently, Okonkwo was a man considered as a hero but ended up a villain who destroyed his village due to his ego and a bigger than life character. His temper and violent behavior made him mistreat his wives and others around him. Mugabe mistreated the whole citizenry and ruthlessly dealt with his opponents and even those close to him, for example, Joyce Mujuru, Edgar Tekere and Emmerson Mnangagwa, just to mention but a few. On the other hand, Okonkwo was single-minded in his image of manliness and abhorred pacifism. Whereas, Mugabe’s penchant for violence is well documented such that at one point he boasted of having degrees in violence.

Okonkwo fought in defence of his people and at the same time, Mugabe’s role during the liberation struggle cannot be rubbished as he led Zimbabwe to independence from white minority rule. During the former’s time, missionaries were more villainous than he was (Okonkwo), kidnapping the leaders without provocation and threatening to kill them, Mugabe walked the same road.

Okonkwo was a victim to his ignorance of other cultures and practices. However, his way of life was the only thing he knew and the new ideas and religion that attacked him from all angles were more than any one person could take. Mugabe’s Christian fundamentalism, moralism , and his homophobic stance are a classic example fitting this narrative. Okonkwo, like Mugabe’s end, was tragic and in the end, the two can neither be classified as heroes, victims or villains entirely. To sum up, Mugabe’s legacy is a conflicted one that will be told in different narratives.