From the 29th of June to the 1st of July 2021, in a video conference, the United Nations Human Rights Committee examined the human rights situation in Togo. In conclusion, a periodic meeting that has become increasingly non-binding for States. Most of the recommendations made are implemented depending on the mood of the leaders, especially Togolese leaders.

Yet again, the ministers of the government of the Togolese Head of State Faure Gnassingbé gave the UN Human Rights Committee the picture of a Togo where everything is well. A habit that no longer surprises those accustomed to the socio-political situation of the Gnassingbe country. Indeed, the reality is quite different.

Togo remains a dictatorship of more than 54 years with a policy of systematic human rights violations and impunity, and the United Nations is content with minimum service even though the situation is getting worse year after year.

However, based on the civil society report, the UN committee has a clear idea of the seriousness of the violations perpetrated against peaceful populations.

This year, the Committee focused on the lack of independence of the judiciary, freedom of expression, the law on demonstrations and the issue of detention conditions.

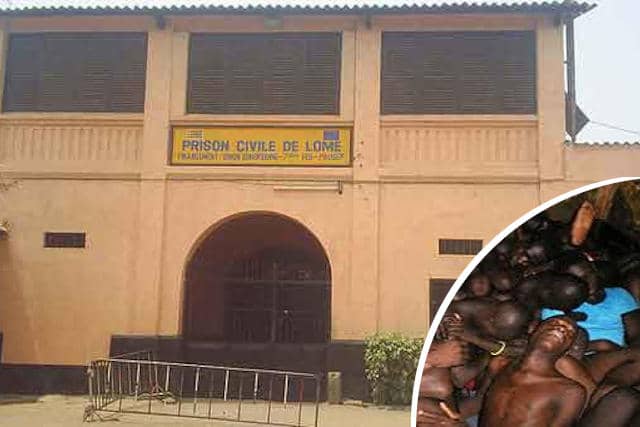

It is common knowledge that prisoners in Togo experience dramatic conditions. The United Nations had already called for the closure of the civil prison of Lomé, which does not meet any standards. As one can imagine, the Lomé prison is still operating as usual. One of the few countries in the world that gives the impression of being above the international community and does not care about recommendations.

Moreover, torture is considered a crime and yet continues to be practised by the security forces on defenceless citizens, without any sanction being imposed on the perpetrators. The culture of impunity is another characteristic of the regime.

In the same vein, in response to a question from the Committee on allegations of torture against Kpatcha Gnassingbé, the brother of the Togolese President was sentenced to 20 years imprisonment for an attempted coup d’état, the delegation stated that he was never the victim of torture. She added that “the pressure put on this case does not work in the prisoner’s favour and does not favour a presidential pardon decision, which remains possible in this case”.

However, it should be recalled that it is this very case that revealed the torture practices in Togo, with the conviction of the State by the Court of Justice of ECOWAS, and Kpatcha Gnassingbé, after 13 years of detention, saw his health deteriorated and risks amputation because of a venous ulcer. He was refused medical evacuation, as well as a presidential pardon, despite the multiple requests made by the Republic’s personal prisoner. Without forgetting the refusal of the Togolese government to respect the ECOWAS court ruling in favour of the release of the detainees as well as the opinion of the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, which called for their immediate release. The experts will rightly say that Togo does not seem to have eliminated torture on a “structural” level.

On the issue of press freedom, it is a return to the dark ages with unfair condemnations and suspensions of newspapers. To this effect, the UN expert stated that the Committee is informed that the High Authority for Audiovisual and Communication (HAAC) is not independent of the executive power. It does not adequately protect journalists and also takes an “extremely high number of sanctions”, including closures and withdrawals of broadcasting licences, because of articles and programmes critical of the government. The HAAC is seen as protecting the executive, she noted, pointing to the “very low volume of information” provided by Togo in its report in this regard.

Moreover, on the pretext of the Coronavirus pandemic, all demonstrations are prohibited in the name of the state of health emergency, renewed every six months. A godsend for a dictatorial state that closed all spaces of freedom, amplifying the violations of the most basic rights of citizens.

In August 2019, the Togolese government amended the law on demonstrations with more stringent provisions, thus making for political parties and civil society organizations activities impossible.

On the 11th of September 2020, UN special rapporteurs on civil and political rights already called on the Togolese authorities on the issue. At the time, no positive reaction was recorded.

Ms Photini PAZARTZIS, Chairperson of the Committee, noted that despite the progress made by Togo, there were still challenges to be met in various areas, including the fight against corruption, the independence of the judiciary, women’s rights, and freedom of expression.

The Human Rights Committee will hold its next public meeting on Friday, 16 July, to hear the Special Rapporteur for follow-up on concluding observations adopted by the Committee following the consideration of the State parties’ reports.