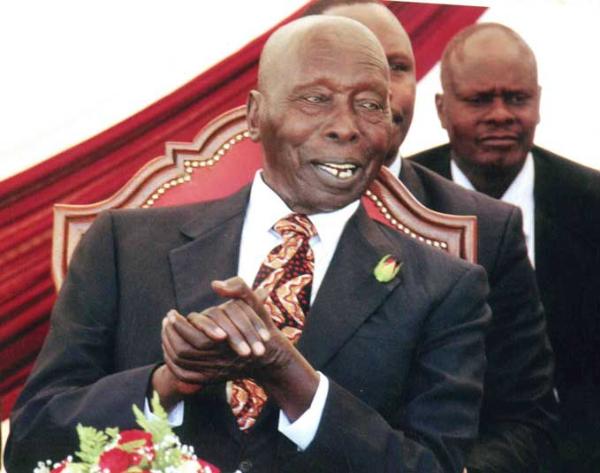

Kenya’s second President Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi died on Tuesday (4th February 2020), aged 95. He was a leader who elicited mixed reactions during his tenure as president, and in his life after leaving office. His death has been no different.

In their usual fashion, Kenyans moved to various social media platforms, following the announcement of Moi’s death by President Uhuru Kenyatta, to convey messages of sympathy, and to reflect on his legacy.

Among what the former president is praised for is his percieved soft spot for the development of education in the country. He supported the construction of various public secondary and primary schools throughout the country, a lot of these were named after him. President Moi also initiated the school milk program popularly known as “maziwa ya nyayo,” that involved provision of milk to primary school kids across the country.

Through his iron-fist rule, President Moi managed to keep a stable nation despite neighboring countries being embroiled in civil wars.

I have however struggled to find positive influences Moi’s regime had on the economy or on the country’s social fabric of the nation beyond these examples. There were definitely a few good things about the man, but the economic plunder and cases of human rights abuses that were the order of the day during his presidency very much overshadowed the little good he did for the country if any.

Then there will be a conversation about Moi’s legacy and comparisons of Kenya under Moi and his predecessors.

So what really is Moi’s true legacy?

Human rights abuse record

When curtains fell on President Moi’s rule one cold December morning in 2002, after his favored candidate Uhuru Kenyatta was floored by the opposition’s Mwai Kibaki, celebrations rocked every corner of Kenya with the exception of the Rift Valley region where the retired president hailed from.

The celebrations were of freedom after 24 years of Moi’s authoritarian rule. During those years, detention without trial, the assassination of political dissidents, torture of opponents, the entrenchment of single-party rule and gagging of free speech was the order of the day.

When he took over power in 1978, Moi reassured Kenyans that his administration would not condone drunkenness, “tribalism”, corruption, and smuggling, problems that were already deeply entrenched in Kenya. His administration also took quick actions against top civil servants accused of corruption, culminating in the resignations of officials including the Police Commissioner, Bernard Hinga. These actions were interpreted by Kenyans as an indication of the dawn of a new era, a conducive environment for adherence to democracy and human rights.

A publication by the University of Florida’s Centre for African Studies titled “Human Rights Abuse in Kenya under Daniel Arap Moi” says that the retired president became more ” interested in neutralizing those perceived to be against his leadership. The issues of corruption, “tribalism” and human rights per se became distant concerns. “

His grand design turned out to be a strategy geared toward the achievement of specific objectives, namely, the control of the state, the consolidation of power, the legitimization of his leadership, and the broadening of his political base and popular support. It turned out this strategy called for little respect for human rights.

By 1981 all the ethnic-centered welfare associations had been banned. These included the Luo Union, the Gikuyu, Embu, and Meru Association (GEMA), and the Abaluhya Union. The president also outlawed the Civil Servants Union (CSU) and the Nairobi University Academic Staff Union (UASU). In 1986 Moi gave a directive for the Maendeleo Ya Wanawake Organization (MYWO), a national non-governmental organization for women, to be affiliated to KANU, and in 1987 officially changed its name to KANU-MYWO. The Central Organization of Trade Unions (COTU), the umbrella body for most of the trade unions in Kenya, had been an ally of KANU for more than two decades, with most of its top leadership frequently selected by KANU, particularly in the 1980s to 1990s. These changes strengthened party-state relations and solidified presidential control of the state. Between 1964 to 1990, twenty-four constitutional amendments were enacted by parliament, all intended to strengthen the presidency at the

the expense of civil rights.

Detentions and political trials, torture, arbitrary arrests and police brutality reminiscent of the colonial era have become common during Moi’s tenure. He perceived human rights generally as alien and Euro centric conceptions inconsistent with African values and culture.

The detention of University of Nairobi faculty members, Willy Mutunga (who would later become Kenya’s first Chief Justice under the new constitutional dispensation) and Katama Mukangi, for what Moi called “over-indulgence in politics” was part of actions meant to silence members of the academia, perceived to be critical of his authoritarian rule.

The pillage of national resources

An expose’ published by Wikileaks laid bare details of how government money was stashed away in foreign bank accounts by government officials working on behalf of the retired president.

The suppressed U.K auditor’s report details how Kenyan state finances were laundered across the world to buy properties and companies in London, New York, and South Africa and even a 10,000-hectare ranch in Australia.

The countries involved in the corrupt dealings include Australia, Belgium, Brunei, Canada, Finland, Germany, Grand Cayman, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jersey, Liechtenstein, Liberia, Luxembourg, Malawi, Namibia, the Netherlands, Puerto Rico, Russia, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Switzerland, the UAE, Uganda, the United Kingdom, the United States and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The intricately detailed report, commissioned by President Kibaki after his 2002 election victory but later suppressed, forensically investigates corrupt transactions and holdings by several powerful members of the Kenyan elite.

The sums are comparable in magnitude to the looting of infamous kleptocrats such as Mobutu (Zaire), Marcos (Philippines), Abacha (Nigeria), Suharto (Indonesia) and Fujimori (Peru).

Transparency International estimates that over USD 3 billion was stashed abroad, by the former President and his closes associates.

While there was hope at the beginning of President Kibaki’s term, these hopes for a better Kenya have since died with the country currently struggling to stay afloat economically. Our foreign debt is at it’s highest levels ever with the government currently resorting to austerity measures meant at reducing public spending, albeit at the expense of service delivery to Kenyans.

Moi and his predecessor Jomo Kenyatta set the stage for the looting of public resources that now seem to have been perfected by successive regimes.

If President Moi had stayed the course he initially set of fighting corruption, ending tribalism and entrenching rule of law, Kenya would be playing in the league of her agemates like Singapore and other East Asian countries now known as the Asian Tigers.

Kenya was economically level with Singapore in 1971. But at the time Moi left office, according to the World Bank, the average Singaporean earned the equivalent of $19,000 a year, while the average Kenyan earned $285 – the same as in 1963.

Even as Kenyans mourn because death is painful, the realities and truths of Moi’s legacy have to be laid bare. Perhaps it’s the practice of singing praises, even for bad leaders, when they die that makes them heatless-rulers. Living knowing that the truths about their reign will be laid bare when they are no longer here to use the powers that be to defend their ill-gotten wealth or their families from public humiliation might be a deterrent for future leaders.